The problem of placebos in research on the impact of social media on people's well-being

Research on the effect of social media on people’s well-being is challenging, for many reasons. In this post I highlight one such reason that is often ignored in experimental research on this important topic: placebo effects.

Note: all views expressed in this post are my own – they do not represent the views of any company or organization.

In short, placebo effects can arise any time there is a difference in expectations about the effect of an intervention on the outcome(s) of interest between the treatment and control group(s) in an experiment.

This is why, for example, in medical research about the efficacy of a new drug there is a treatment group (which receives the drug) and a control group (which receives a placebo pill) so both groups think they have taken the drug and have the same expectation about its benefits. Ideally a “double blind” procedure is also used so neither the participant nor the researcher administering the study is aware of which condition people have been assigned to. In this way, any effect of treatment can be more confidently attributed to the drug itself rather than differences in expectations.

In psychology research investigating the impact of social media on people’s well-being, however, controlling for people’s expectations is more challenging – double blind experimental designs are not possible. That is, people know exactly which group they have been assigned to (e.g., stop using social media) and bring with them expectations about what impact that treatment should have on their well-being. If people in the treatment and control groups of an experiment have different expectations about what effect using (or not using) social media has on their well-being, then causal inference is necessarily undermined because the possibility of placebo effects has not been accounted for.

Solving the problem of placebos

Solving this problem is challenging but critical to the scientific integrity of research on the effect of social media on people’s well-being.

Practically speaking, it doesn’t really matter if people benefit from using (or not using) social media due fully or in part to placebo effects - they still benefit either way.

But scientifically speaking, it matters whether the causal mechanism is actually the treatment or expectations about the treatment, and without accounting for placebo effects we won’t be able to untangle this important question.

So how do we solve this problem?

As outlined by Boot et al. (2013), there are a few approaches:

- Explicitly assess expectations.

- Carefully choose conditions and outcomes that are not influenced by differential expectations.

- Use alternative designs that manipulate and measure expectations directly.

For example, the possibility of differential expectations in already published studies could be tested by recruiting samples of participants from the same population that was used in the study, describing the treatment/control condition(s) that were used, and then assessing peoples expectations about their impact on the outcome(s) that were measured. If there is evidence that differential expectations are consistent with the pattern of results found in the published study, then it would suggest that placebo effects have not been adequately accounted for. This same kind of procedure should also be used before executing a study, to help choose the best treatment/control tasks and outcomes so expectations are the same across them.

Takeaway

Given that we are not able to execute double-blind studies as in clinical trials – and benefit from the increased confidence about causal inference that those experimental designs afford – psychology studies on the effect of social media on people’s well-being must adequately account for expectations before definitive statements about causality can be made.

Note: full R Markdown used for this post is available @ https://github.com/ryansritter/placebos

Recommendations for further reading

- Boot et al., 2013 - Overview of the problem of placebos in psychology research.

- Kross et al., 2021 - Overview of the evolution or research on the relationship between social media and well-being.

- Ernala et al., 2022 - Mindsets matter: How beliefs about Facebook moderate the association between time spent and well-being

Data appendix

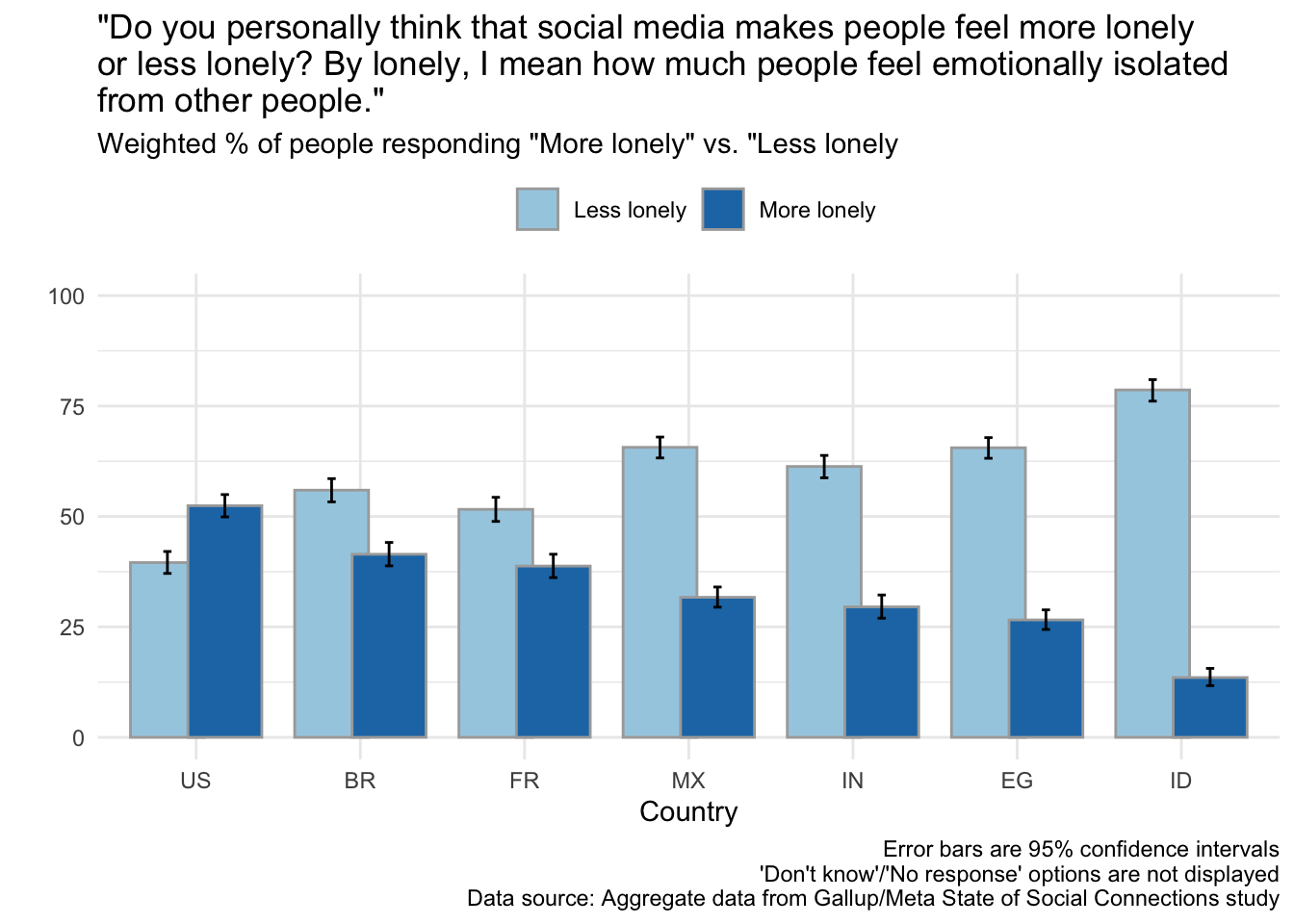

In 2022 Meta and Gallup collaborated with some of the world’s top social scientists on the State of Social Connections study, which offers a first-of-its-kind look at how social connections vary across different geographic regions.

The data includes nationally representative samples of adults (age 15+) in 7 countries: Brazil (BR), Egypt (EG), France (FR), India (IN), Indonesia (ID), Mexico (MX), and United States (US).

Check out these links to learn more:

- Report of main findings

- Methodology report

- Survey instrument

- Multiple regression tables

- Aggregate data download

- Micro data request form

In this notebook I used the aggregate data (available for public download using the link above). The full item wording and response options are:

“Do you personally think that social media makes people feel more lonely or less lonely? By lonely, I mean how much people feel emotionally isolated from other people.”

- More lonely

- Less lonely

- [Don’t know/No response]